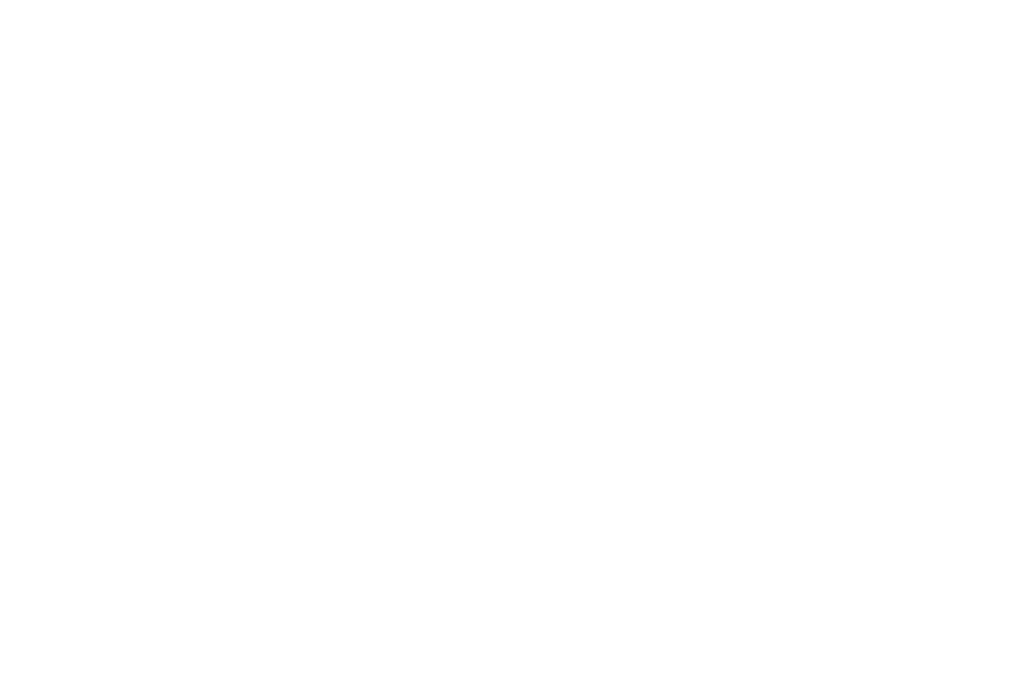

Air France 447 wreckage

Seven years ago today, an Air France Airbus A330 failed to arrive in Paris after an overnight flight from Rio de Janeiro. Two hundred and twenty-eight people died. So it is a particularly poignant case of “the more things change the more they stay the same,” that the airline industry is still wrestling with the issues raised by that accident and revisited repeatedly since then.

The loss of EgyptAir Flight 804 over the Mediterranean is the most recent re-ignition of the conversation. On May 20th, the Airbus A320 with 66 people on board appears to have crashed in the sea and the recorders have not been found.

“What is critical for us is [that] everything is done to find the black boxes,” Fabrice Brégier, chief executive of Airbus told the Wall Street Journal at a meeting with journalists earlier this week.

It took two years and several million dollars to retrieve the voice and flight data recorders from Air France Flight 447, a success that the chief investigator Olivier Ferrante told me was partially attributable to “luck.” That the whimsy of fate should play a lesser role in future accidents however, remains a quixotic goal.

At the annual general meeting of the International Air Transport Association in Dublin, safety director Gilberto Lopez-Meyer, said the industry is examining many solutions but the two most likely are an expansion of technology that allows for the live streaming of data from an airplane in distress and an older technology, a recorder encased in an airfoil that self-ejects in a crash. It can fly, it can float and it can transmit its GPS location. So even in a case where the plane cannot be found, at least the recorders would be.

In 1999, Rob Austin, an engineer with DRS, the company that makes the deployable recorder, wrote about how beneficial the product would be in an imaginary case where a plane broke up “over deep ocean where the exact location of the aircraft is difficult to track.” This was 15 years before Malaysia 370 nearly duplicated the scenario he described.

A deployable FDR ejects in a crash

While ejectable recorders have been used on military and industrial aircraft for more than 30 years, use on commercial aircraft remained in the discussion phase until earlier this week when Airbus announced it would install them flight recorders on all its airliners from the narrowbody A320 to the A380 jumbo jet and all those in between.

“Unfortunately this has taken much more time than we all would like,” said Blake van den Heuvel Director of Business Development at DRS Technologies, the company that makes them. He told me today about the long road from Air France 447 in 2009 to the Airbus announcement.

“Air France 447 caused the phone to ring off my desk almost continuously,” he said, adding that interest “ebbs and flows, timed to the major events that have taken place and there have been a number.”

Now ships in the Mediterranean looking for the Egyptair flight are in a race against time, trying to find the black boxes and the questions being asked of IATA’s safety director are the same ones van den Heuvel got all those years ago.

Along with deployable recorders, is another very different idea, not recovery of a physical recorder but the downloading somewhere on earth of triggered data from an airplane in crisis regardless of whether the airplane itself is found.

And while sending flight data into the cloud is also not a new idea – a relatively tiny slice of information like it is in the transmission of ACAR’s data – it is far from achievable in the short term and comes with a host of problems and “what if’s” from the simple, “who owns and controls data the cloud?” to bandwidth limits for the reams of information that is captured on a modern flight data recorder and cockpit voice recorder.

At the afternoon round table of airline executives, all five airline bosses insisted not being able to locate EgyptAir was “disgraceful” (Emirates boss Tim Clark’s word).

“We’ve got to do a lot better than we have been doing,” Clark said.

“But you are the ones who have to do it,” CNN’s Richard Quest, the moderator interrupted.

“I have not been vocal on tracking because I pride myself on our ability to do that,” Clark replied before adding his airplanes report geographical position “within 10-15 minutes.”

At that rate, an airliner can cover one hundred fifty miles putting the airplane well into what the experts call a geographic “cone of ambiguity.”

In other words, while Clark may say his airline has already solved the problem should an Emirates airliner go missing while transiting a great expanse of ocean finding it could prove just as difficult as in previous accidents.

Many ideas get churned up following a catastrophe and chief executives wring their hands. But when proven solutions are debated for nearly a decade air travelers are right to demand why more is not being done. If this latest lost airplane doesn’t prompt a solution, which one will?

Author of The New York Times bestseller, The Crash Detectives, I am also a journalist, public speaker and broadcaster specializing in aviation and travel.

Christine,

How very “on point” you are here with both the call for decent location tracking and ejectable flight data recorders.

For years I ran a GPS tracking sales and service business. One large client had both “ground based” (cars and trucks) and “airborne” (helicopter) company assets.

The client bought every single tracking device for a ground based asset I ever proposed … even garbage collection trucks, but never allowed even a test and demo installation of the choppers. “Oh we don’t need that, the FAA tracks them for us.” Bzzzt.

Mr. Clark? Sorry but you’ve missed some big points and oversimplified a complex problem here.

The “Reams of Data” argument against live-streaming is a complete red herring. It simply is not real. FDR data is very low density numerical data that does not take up much bandwidth at all. The IFE systems and in-flight WiFi consume many orders of magnitude more bandwidth than any live stream of cockpit audio and FDR info ever would.

The real issue is, as you have alluded, who owns the data. Pilots and airlines do not want their day-to-day activities exposed to third parties for any sort of independent analysis. Now, any analysis is only done if something goes wrong.

Live off-board storage of data is completely within the state of the art. It is a political problem.