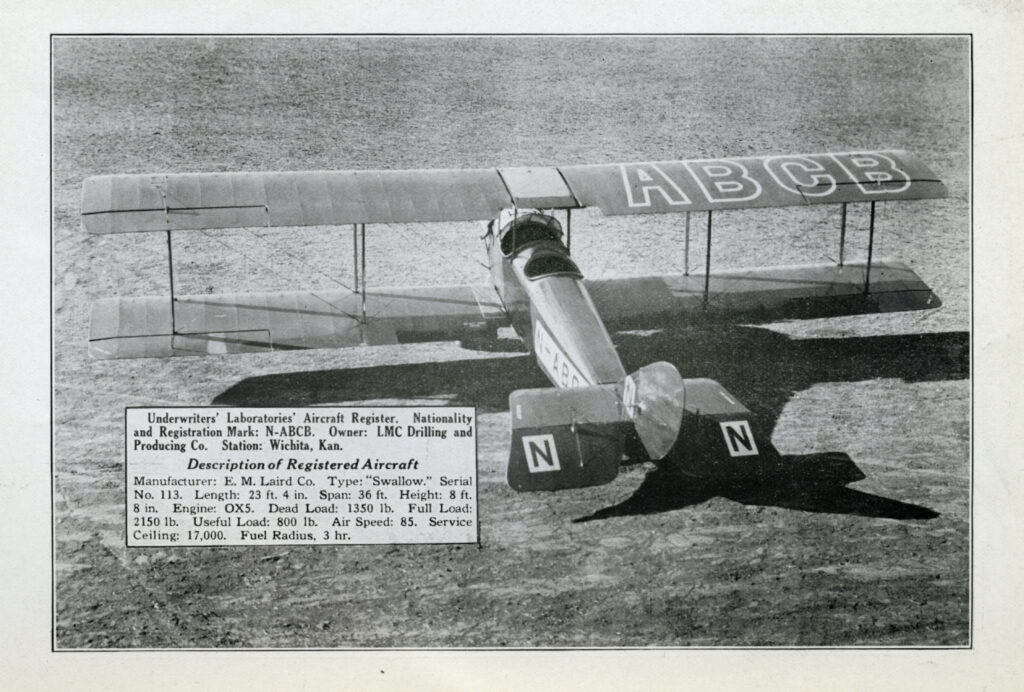

Photograph courtesy of Underwriters Laboratories

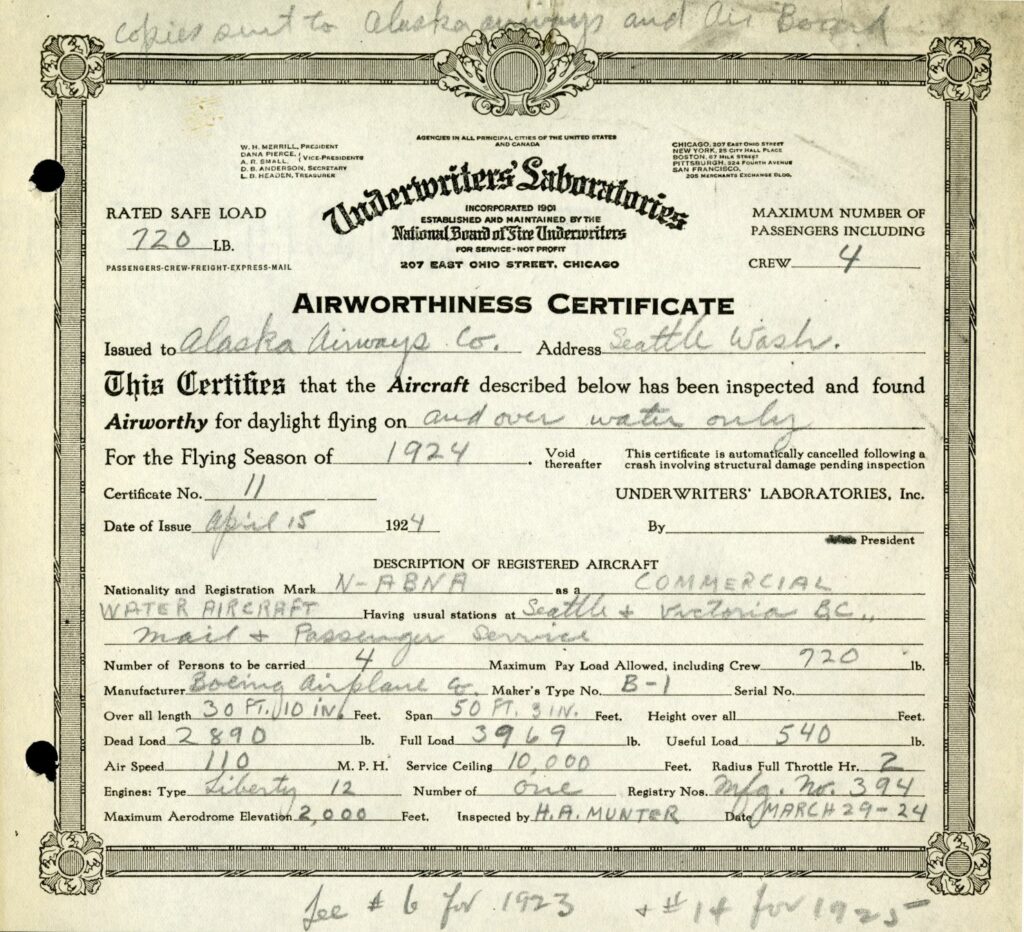

In the early days of aviation, those with the second most to lose in a crash – the first being the occupants of the airplane – took responsibility for making sure the plane and its pilots were safe. That entity was not the government, it was the insurance companies.

“They couldn’t prevent pilots from stunt flying and the planes would crash and they would pay out,” said Rachel Madden an archivist with UL in Illinois, also known as Underwriters Laboratories. The National Aircraft Underwriters Association asked UL to register pilots, to create airplane manufacturing standards and to inspect and certify the finished products.

Between 1921 and 1925, UL employed 33 inspectors under the supervision of Major R.W. “Shorty” Schroeder a mechanic, test pilot and a multiple world record holder for high altitude flights.

UL had a short reign because in the mid-1920s people started to realize flying was going to be big. It was going to cross borders. It was going to require infrastructure. It was going to need the government.

“People were looking to the feds and saying ‘We can’t have a third party doing this.’” Madden explained.

The industry got its wish. Soon the federal government would take responsibility for assuring safety with notable success.

How the FAA does its job, and how much it has shed its oversight to the companies it ostensibly oversees came under scrutiny with the crashes of two Boeing 737 Max airliners within five months of one another in Indonesia and Ethiopia. That’s because it appears that Boeing design decisions contributing to the disasters were inadequately analyzed by Boeing and insufficiently understood by the FAA.

The fallout prompted some of us who have been involved in aviation safety to consider; does UL’s history in airplane certification provide a template for the future? In an opinion article I wrote for the Chicago Tribune, I pose these questions; Is there a role for private labs as independent assessors of products seeking certification? Should manufacturers bear more of the burden of paying for these tests?

The fallout prompted some of us who have been involved in aviation safety to consider; does UL’s history in airplane certification provide a template for the future? In an opinion article I wrote for the Chicago Tribune, I pose these questions; Is there a role for private labs as independent assessors of products seeking certification? Should manufacturers bear more of the burden of paying for these tests?

As the essay cannot be accessed in many countries where my readers reside, I am restating the idea here.

“The one document that goes in through the front door of the FAA’s headquarters and comes back out and in the transition gains the greatest economic value is a type certificate. You can sell that airplane anywhere in the world.” — Sandy Murdock

Manufacturers seeking FAA certification for their products are given authority to act as the regulator in a program called delegated authority. (Known as ODA) With the burden of oversight of many tasks now removed from them, the FAA needs fewer hard-to-find, highly educated, highly specialized engineers and scientists. In a congressional hearing shortly after the second Max crash, then-acting FAA Administrator Daniel Elwell said reclaiming that authority would require an additional 1.8 billion to the department’s budget and a 10-thousand person increase in its staff.

Clearly the trend was going in the opposite direction because in the fall of 2018, just around the time of the first Max disaster, even more power was given to airplane manufacturers in a little-noticed part of the 2018 Reauthorization Act.

The ODA certification program explains how the Max was given the FAA’s stamp of approval and sold to airlines around the world. What neither the FAA nor Boeing realized at the time is that they did not know how new flight control software would impact the plane’s flying characteristics, according to a report by the Joint Aviation Technical Review Board.

Christopher Hart

“We identified shortcomings,” Christopher Hart, who chaired the review board told me. Aviation has evolved “beyond what yesterday’s system can handle.”

Just how critical the shortcomings depends on who one asks. Senator Richard Blumenthal, a member of the Senate Commerce Committee told me, “No question, the current system is broken and it needs reform urgently and immediately.”

While Hart says that characterization is much too dire.

“While I certainly agree the certification process must be improved, I do not agree that a system that has played a major role in producing the exemplary safety record that the industry has enjoyed for the last two decades is broken.”

Nevertheless, Hart does agree it is time to look at alternatives. “Let’s look at Plan C to see if there is another way to do it.”

Plan C, came from a discussion I had with Sandy Murdock, an aviation specialist who, as the former deputy administrator of the FAA, is no stranger to the complex workings of aircraft certification.

“There is no reason why an organization like the FAA should have to hire PhDs and have enough technical people to keep up with Boeing,” Murdock said. “We should have Underwriters Labs do the work and have Boeing pay for it.”

With that in mind, I called Underwriters for a response and received a quick, “We will need to sit this one out,” from communications director Michelle Press. Okay, so this is not a debate a 125-year old non-profit wants to wade into, I get it. Anyway, Murdock was using the name generically.

Across the land, private engineering, chemical, materials and software labs test everything from batteries to tires offering hyper-specialization to manufacturers who recognize the value of fresh-eyes peer review (or need it to get certificates or insurance). Independent labs are free from manufacturers’ creation-bias and bottom-line focus that appear to have prevented Boeing from discovering the shortfalls in its 737 Max.

When I spoke to Eric Proegler, president of the Association for Software Testing he told me it is possible that the inadequate testing of modified software on the Max highlighted by Hart’s team might have been detected had it been subjected to outside analysis.

“Because software is invisible, it’s a different thing than testing airframes. There are many more possible states that software can be in.” Proegler explained, “It is hard to simulate every possible condition. It takes a lot of analysis to simulate and it is unlikely that regulators can do it.”

If thorough testing requires time and expertise which always adds up to money, should that expense be paid for by the beneficiary of the certification? Let me be more specific.

If thorough testing requires time and expertise which always adds up to money, should that expense be paid for by the beneficiary of the certification? Let me be more specific.

In 2017, the year the Max made its first commercial flight, it was already the fastest-selling airliner in Boeing history. Boeing closed out that year with record operating cash flow and $93.4 billion in revenues.

“The one document that goes in through the front door of the FAA’s headquarters and comes back out and in the transition gains the greatest economic value is a type certificate,” Murdock said. “You can sell that airplane anywhere in the world.”

Until you can’t.

Boeing isn’t there yet. But the nine-month grounding of the Max has had devastating consequences on the company, Consequences that are rolling through the global economy like the waves generated by boulder tossed into a pond.

Photograph courtesy of Underwriters Laboratories

With the effectiveness of the FAA’s oversight now in question, regulators around the world are questioning whether to continue honoring certification reciprocity, which aviation consultant Richard Aboulafia says, “Is hanging by a shred right now.” Just last week, Dominic Gates of the Seattle Times reported Canadians are considering if the troubled MCAS software system on the Max should be removed before the plane is returned to flight.

All of which makes it even more important to learn from the certification failures exposed by the Max, and explore some new, maybe even revolutionary ideas for how to do it better.

Author of The New York Times bestseller, The Crash Detectives, I am also a journalist, public speaker and broadcaster specializing in aviation and travel.

“All of which makes it even more important to learn from the certification failures exposed by the Max, and explore some new, maybe even revolutionary ideas for how to do it better.”

I agree that the certification process has been a deadly failure for many years now, precisely because that task was given to a govt bureaucracy.

We have only to look at the tragic accidents caused by defective designs (yet, approved by the FAA) of the DC-10 cargo door, the DC-10 hydraulic control system, the B-737 single rudder PCU, the MD-11 dynamic instability in the pitch mode and the FAA’s political approval of the French made ATR-72 even though it had already crashed in Italy as a result of that plane’s inability to handle routine icing conditions. And, the near disasters of the B-787’s failure to contain a battery fire.

Turning over the airliner certification process to a private enterprise company would be “revolutionary” only in the sense that doing so has been resisted by politicians and bureaucrats for so long. Historically, product design, testing and approval by an independent private company, as this article points out, has been around a long time and has been very successful.

In my concurring opinion, many things now done by govt bureaucracies could and should be done instead by appropriate private enterprise companies. The process would be far more efficient and successful and freed of the political motivations that too often are present when it has been done by a govt monopoly agency.

I enjoyed your story. Delegating responsibility is not the problem, in my opinion. The problem is poor communication and lack of effective management controls at Boeing and the FAA. Software developers and engineers have millions of person years of experience finding and preventing defects in designs and implementations and managing changes to minimize the risk of uncontrolled changes. I feel sure Boeing software developers, engineers and line managers understand how to do this as well as almost anyone on the planet. Ditto for their counterparts at the FAA. And also that they completely understand the concept of “Andon” http://bit.ly/34rEUk8 that W. Edwards Deming and others pioneered shortly after WWII. The probability that software developers, engineers and line managers at Boeing did not understand the risks inherent in the flawed design changes for the Max is *zero* in my opinion. If you believe that then the problem isn’t so much about detection and who does it as making sure that the people who detect problems really are empowered to stop production when they suspect or discover a defect that threatens success. I suspect Dennis Muilenburg believes this and is making changes to the org structure at Boeing to make sure defects of the type that led to the grounding of the Max are not downplayed or short circuited by higher level managers. The “holistic approach” https://on.wsj.com/2Dp2dit that Stephen Dickson and his FAA colleagues are considering is encouraging if it ultimately includes credible support (vs lip service) for the start to finish open dialog Dickson talks about and for an effective Andon System that aims to stop production and fix defects *before* stuff happens, not after. Mark McEnearney, Software developer and tester (retired), Arlington, Virginia

I can offer another example from a different sector; utility regulation (specifically water supply and sewage treatment) in the UK.

The regulatory environment in the UK specified that the economic regulator of the privatised water industry could require companies to appoint “reporters” – industry specialists who could comment on data collection methodologies, civil engineering processes and the validity of engineering choices from an economic viewpoint. These “reporters” would be appointed and paid for by the company, but would owe a legal Duty of Care to the regulator.

In practice, this meant that major civils consultancies (and some smaller sector players) undertook this work. Their reports to the regulator became a central part of the reporting regime and (after some initial settling down) became an important part of the process.

However, in the fullness of time, the water companies became disenchanted with the process, seeing it as a major regulatory burden. They made sufficient waves for a new incumbent at the top of the regulatory body to decide to dispense with comprehensive independent reporting. This was fine until disquiet arose over the

conduct of some major infrastructure projects, especially connected with the London Ring Sewer and Thames Tideway projects.

This work isn’t safety-critical (at least, not directly). But it had an impact on the bottom line in terms of the bills presented to customers; and for about ten years, the regulator put a lot of store in the information and opinions offered by these reporters. It certainly avoided regulatory capture, as the regulator always had access to independent opinion; and there was always a range of opinions and industry interchange to help give assurance that opinions were honestly expressed. It is possible.

Thank you, Interesting article.