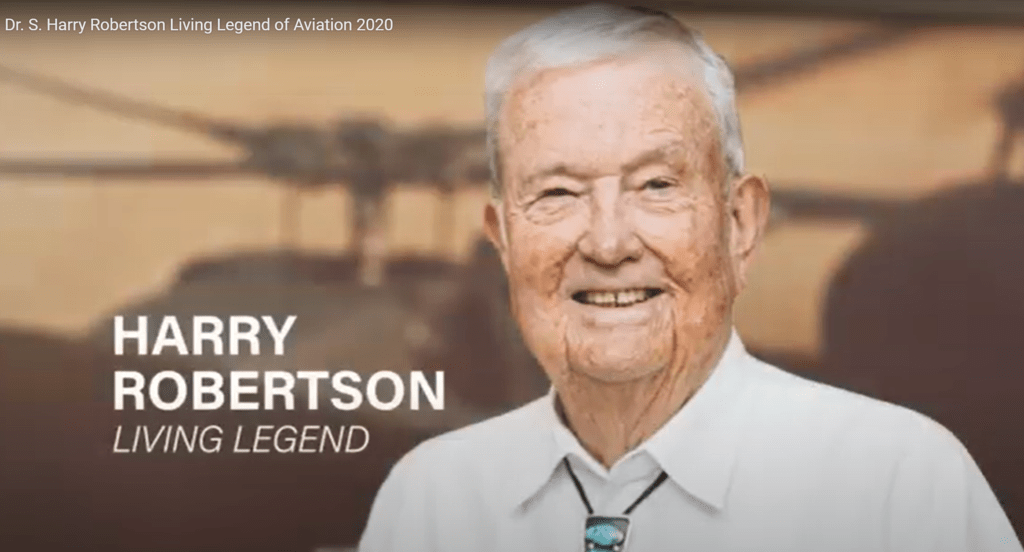

Robertson was honored in 2020 by the Living Legend of Aviation organization.

If safety professionals are underappreciated by the beneficiaries of their labor it could be because their work is hard to assess. Or, as retired air accident investigator Ron Schleede explains, “You can’t count the accident you prevented. You can’t calculate the lives you save.”

And while that’s often true, Harry Robertson, who died on October 9th, did interrupt death. He did this by separating air accidents from the single largest consequential hazard, a post-crash fire. And he accomplished that by eliminating ruptured fuel tanks and spilled fuel the largest factors in post-crash fires.

“Most severe army helicopter crashes resulted in fires, accounting for over 40 percent of fatalities,” said Retired Army Colonel Dr. Dennis Shanahan. “During Vietnam, most pilots and their crews faced this harsh reality on nearly every flight,” he said.

As an Air Force helicopter pilot in the fifties and sixties, Robertson lost friends in some of these post-crash fires which led him to his life’s work.

In a video interview, Robertson explained, “Because fire was as bad as it was, something had to be done to control the fire environment.”

With money from an Army research grant, Robertson began test crashing aircraft and fuel system components, filming the destruction to watch again and again in slow motion. “It’s very important to have evidence,” he said, “to see what broke, because when you know what broke then the challenge comes up to figure out how to fix it.”

While the road between a good idea and a viable company can be long and difficult, Robertson was successful in creating fuel tanks and fuel systems that were resistant to impact and projectiles. In the 1970s, his company, Robertson Fuel Systems was providing what came to be known as “Robbie” tanks for use on military helicopters. Later they would also be used on unmanned aircraft and armored ground vehicles. Crash-resistant fuel tanks are now being offered for use on civilian helicopters.

While the business was growing, Robertson started teaching what he knew, creating the first of its kind, Crash Survival Investigators School. These were the early days of the field of “survival factors.” David Hall, a naval aviator, flight engineer and safety specialist met Robertson taking one of his classes. Eventually, he went to work for Robertson.

“This was about the inside of the airplane,” Hall remembered of the survivability for investigators class. “We got flight attendants, military people, all sorts of interested people from around the world who were interested in this subject.”

Even today, outside of the air safety community, survivability is often overlooked, certainly from the public which largely believes “you crash/you die” and even sometimes from those who should know better like certain airline executives.

But to professionals like Schleede, Robertson’s insight into survival factors was valuable and illuminating. Schleede had also been a student of Robertson’s survivability course. Not long after that, while investigating a general aviation accident in the fall of 1977, Schleede found himself thinking about something he had learned from Harry.

The pilot of a Piper Cherokee with 3 passengers aboard had taken off from Carlsbad, New Mexico airport then immediately attempted a return but landed short of the runway. In the process, the landing gear was torn off and the flexing of the wings caused a pipe from the tank to pull free so that fuel sprayed into the cockpit causing a fire. Everyone survived the landing but the pilot was killed in the fire and others were badly burned.

“The airplane was hardly damaged,” Schleede recalled, “I couldn’t figure out why it caught fire right under the feet of the pilot.” Schleede noticed the pipe was a straight run and remembered Robertson had demonstrated that making an “S” turn in the gas line could protect against its dislodging under stress.

Over the course of his lifetime, Robertson was a generous benefactor, providing money for a scholarship for investigators interested in learning more about fire safety. The man who in his youth could not afford to attend Embry Riddle Aeronautical University, went on to fund several air accident schools, an accident investigation laboratory and a research library at the Prescott campus. (Notes and documents from my books, The Crash Detectives and Deadly Departure reside at the Library of Robertson Aviation Safety Center.)

Robertson received the Jerome F. Lederer Award of the International Society of Air Safety Investigators and was enshrined in the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 2011 where NAHF president and CEO Amy Spowart said of him, “Harry, for as big as he was in aviation, was an even bigger human.”

People who knew him described him as “driven” and “a character”. Spowart called him, “immensely talented and unnervingly humble.” For those who never knew him or will never know his role in keeping them alive, Schleede’s description applies. “Harry was a hero.”

Author of The New York Times bestseller, The Crash Detectives, I am also a journalist, public speaker and broadcaster specializing in aviation and travel.

The article does not mention that Harry also donated $1 million to the Flight Safety Foundation around 2008. LIt was negotiated by the Ed Stimpson, the Chairman of FSF at the time

Thanks Bill for adding this information. Even with this addition, we cannot approach a comprehensive list of Harry’s contributions.