NOTE: This post has been updated to reflect new information from Boeing regarding quality control inspections. Read through to the end for details.

I’m all for the National Transportation Safety Board doing its job, and planning, of course, to dig into into the final report a year or two from now. But for any curious air traveler, engineering geek or disaster buff, what happened to Alaska Airlines Flight 1282 last month is no mystery. The report aligns quite neatly with a prediction more than a year ago on Ed Pierson’s podcast Warning Bells.

The 737 Max production line in Renton, Washington was “chaos at its best”, according to Chris Lee, a retired Boeing mechanic and a guest on the podcast. As Boeing speeded up production of the Max, mechanics would sometimes be unable to finish sequential tasks before the next one began. This was problematic, according to Lee.

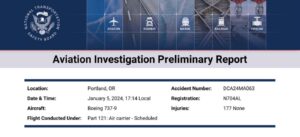

But first, let’s have a look at what the NTSB’s preliminary report released late Tuesday has to say about what happened in the months before the Alaska 737 Max shed a chunk of the passenger cabin triggering the harrowing flight on January 5th.

The fuselage that would become Alaska’s airplane arrived from Spirit Aerosystems in August 2023 with the door plug installed and rigged. However, on inspection, five damaged rivets were found on the frame in front of the plug. Look for the orange ribbons to the left of the circled numbers in the photo above. The repair involved the door plug because it had to be opened for the work to be done. So all four bolts holding the plug in position were removed.

Once the repair was done, a photo was taken documenting the work and exchanged among Boeing team members via text. The blue circles in the photo below show where the bolts should be but were not installed. (The 4th attachment point is not visible due to the insulation in the left top corner.) The NTSB report does not mention if the blue circles were in the original text message. (That would be its own story.) So while waiting for clarification I’m assuming the NTSB added the circles to provide clarity.

Following this, the insulation and walls were installed over the plug so that the hardware or lack of it was no longer visible.

This is the documented order of events provided by the safety board.

Now here is how former Boeing mechanic Lee predicted this very kind of event back in 2022 as a guest on the Warning Bells podcast.

“A lot of times what would happen is there would be a problem at a certain area of the airplane that would get covered up,” while the mechanic waited for materials to arrive or engineering support. Lee and Pierson were talking about out-of-sequence work, the process of continuing with the build while waiting for something specific.

Resolving Spirit Aerosystems bad rivets wasn’t exactly out of sequence, it was characterized as a non-conforming part. But whatever you call it, it played out just as Lee described in the out-of-sequence work scenario. The person doing the fix, would have to “remove panels or he’ll have to take apart another section of the airplane just so he can get to work where he needs to work and complete a job. And sometimes what happens is, when he puts whatever he has to remove back into place, it may not be in the original configuration. The screws may not be torqued down correctly. It’s a list of things that can go wrong.”

The NTSB reports Spirit Aerosystems workers fixed the rivets and Boeing closed up wall, finishing it off with the photo that shows the bolts were not reinstalled. Investigators are continuing to track what documents authorized the opening and closing of the door.

The NTSB reports Spirit Aerosystems workers fixed the rivets and Boeing closed up wall, finishing it off with the photo that shows the bolts were not reinstalled. Investigators are continuing to track what documents authorized the opening and closing of the door.

An earlier account posted to Leehamnews.com from a source familiar with the process who did not want to be identified noted that Boeing workers engaged in a series of texts which seemed to put the write-up decision into the context of what would trigger a quality assurance inspection. The person characterized the text exchange this way: “coordinating with the doors team to determine if the door will have to be removed entirely or just opened. If it is removed then a Removal will have to be written.” A removal, this person notes would require formal sign-off showing that the airplane has been restored to drawing requirements.

Not everything this person mentioned in the post left on the Leeham site has been confirmed, but a lot has. More to the point, there’s a distinction but no difference between opening the door and removing it in terms of safety. In both cases, the retaining bolts are removed.

Not everything this person mentioned in the post left on the Leeham site has been confirmed, but a lot has. More to the point, there’s a distinction but no difference between opening the door and removing it in terms of safety. In both cases, the retaining bolts are removed.

For several years Boeing had been engaged in a well-documented campaign to reduce quality control inspections. It stepped back from that one week after Flight 1282 when Stan Deal, the president of Boeing Commercial Airplanes announced the company would be “taking immediate actions to bolster quality assurance and controls across our factories.”

There would be more quality inspections, airlines could conduct their own inspections and the company would seek guidance from an independent assessor. Read the details here.

The NTSB’s preliminary report leads any thinking person to conclude the actions Pierson and Lee worried about in 2022 predicted the near disaster on flight 1282. It is a little harder to predict whether Boeing’s newfound appreciation for double and triple-checking the countless steps involved in building safe airplanes will be long-lasting.

I’m not predicting it will, but I’m not ruling it out either. How about you?

“A Rambling Shambling Disaster” Anonymous Insider Reveals How 737 Max Flew with Door Plug Unbolted

Author of The New York Times bestseller, The Crash Detectives, I am also a journalist, public speaker and broadcaster specializing in aviation and travel.

Thanks Christine, well done.

Hi Christine:

Even before the TSB published its advanced report on the 737 Max 9 incident, I believe that most informed individuals engaged in the aerospace or air carrier operational world – could have narrowed down the matter without too much difficulty – to assembly, or maintenance control failure,.

As a retired Canadian regulatory official, and having had close knowledge of how both the FAA and Transport Canada chose to alter the manner by which they regulate the aviation industry in the late nineties and early two-thousands, this eventual outcome could have been predicted many years ago – as both agencies handed over much of their respective regulatory inspection oversight to its Certificate holders.

So, with a pullback of, hands-on regulatory inspections, normally conducted by regulator staff, coupled with ceded and divested authority, through diluted inspection policy, and an over reliance on a universally adopted, but at the time, theoretical but unproven, Safety Management System (fox in charge of the hen house), the regulators placed firm regulatory safety controls in the hands of industry without the requisite independent scrutiny needed to assure the flying public of a safe operational outcome.

From industry’s perspective the new system meant less regulatory intrusion, cost savings, and greater management control of the regulatory environment.

From the regulator’s perspective, the new trajectory would result in considerable operational savings in regulatory resources, by reducing both in-house Inspectors numbers and qualifications standards necessary to regulate the civil aviation industry: Considered to be – a win-win for all.

In that regard, it is my view that until such time as the regulators return to their respective and proven oversight systems to previous numbers and policies – incidents and accidents of this nature will continue to occur going forward: This, as more of the same will continue to foster the same uncontrolled safety results.