My mother-in-law Mary Schembari could probably count on her arthritic fingers how many times she has flown on an airplane. In the 40 years she has been in my life, I don’t recall that she ever did. Only stories of two trips to Europe led me to conclude that she probably boarded an airplane a few times in her long life.

Still, she needs no frequent flyer miles to have her place sealed in aviation history. She welded airplane parts for the Corsair Navy fighter plane, putting her among the six million women in America who supported the defense industry during World War 2. These women were awarded a Congressional Gold Medal in 2019.

They are called Rosies – after the 40s era Rosie the Riveter recruitment slogan. But Mary never liked that they were all lumped together as “riveters.” She was a welder, trained and tested and working on critical aviation parts. It was a source of pride.

In 1942, my mother-in-law was a 17-year-old high school senior when she and two classmates were offered the opportunity to learn how to weld. She said “yes” with one thing in mind, goofing off. She was living in the International Organization of Odd Fellows’ Orphanage, in Sunbury, Pennsylvania.

“We figured we would get out of class,” she said of her spur-of-the-minute decision.

“We had to walk up the railroad tracks to a shack,” Mary said, where the welding lessons were given. “They gave you two pieces of metal and you had to put a bead on that does not show to the other side and it is going to hold the two pieces together.”

With the obliviousness of teenagers in every time and place, Mary gave little thought to the importance of the work or what impact these lessons might have on her future.

“I mean we did this as a lark,” Mary explained. “We didn’t realize we were going to have a test. So, we all took the test and I passed it. My two friends didn’t but I did.”

In 1943, when Mary graduated high school, her older sister Jo, then a telephone operator in Wallingford, Connecticut drove back to the orphanage to collect her little sister and bring her to Connecticut. Mary would go to work with another sister, Lucy, at Navy contractor, Chance Vought, a division of United Aircraft. The company was producing the FU Corsair in Stratford and needed all the help it could get.

In early summer she aced the welder’s exam and started working for $1.25 an hour helping build the single-engine, gull-wing fighters.

“Anytime you talk about World War II airplanes, the Corsair is always going to be at the top,” said Len Roberto, a member of the board of directors of the Connecticut Air and Space Center. “It’s a world leader, “there’s no way you can mistake this plane for anything else other than a Corsair.”

Mary didn’t know a Corsair from a crossword puzzle but she knew her job. She purchased tools and a toolbox. She settled in at a welder’s bench. Another welder, she recalled his name as Sullivan but everyone called him Sully, taught her the specifics with parts that were light and easy to handle. Sully also advised the teenage new hire to read a newspaper every morning; advice she followed for the rest of her life.

Considering the ambitiousness of the work – turning out warplanes at a rate of hundreds a month, Mary remembers the factory as neither fraught nor frantic. It was convivial. Supervisors cautioned everyone to do the job right, after all, lives were at stake but the mood at the plant was generally light.

“We had the foreman who would come around and check our work and say, ‘That’s a good weld, Mary.’ Or ‘You know that wasn’t so great,’” she told me. “They kept after you to improve, to stop the fooling around and concentrate on what we were doing. There was a lot of flirting going on in the factory.”

There were opportunities for those who were interested to learn about the planes they were making. Now and then there would be a ceremony celebrating the completion of an airplane that was notable for one reason or another. Workers would leave their benches and go outside. The plane would be there and someone would make a speech. “Maybe this was the 500th plane or whatever it was and we would go out there,” Mary said.

In truth, Mary confessed, the official ceremony was the background to a higher priority among the women. “We just went out there and kibitzed.”

Whe she first arrived in the state, she and her sister lived in a boarding house with sisters from Massachusetts who were also working at Chance Vought. Lucy and the Massachusetts sisters worked nights but because Mary was not yet 18 she could only work days. So she and Lucy hot-sheeted. Mary got the bed at night and Lucy climbed in in the morning.

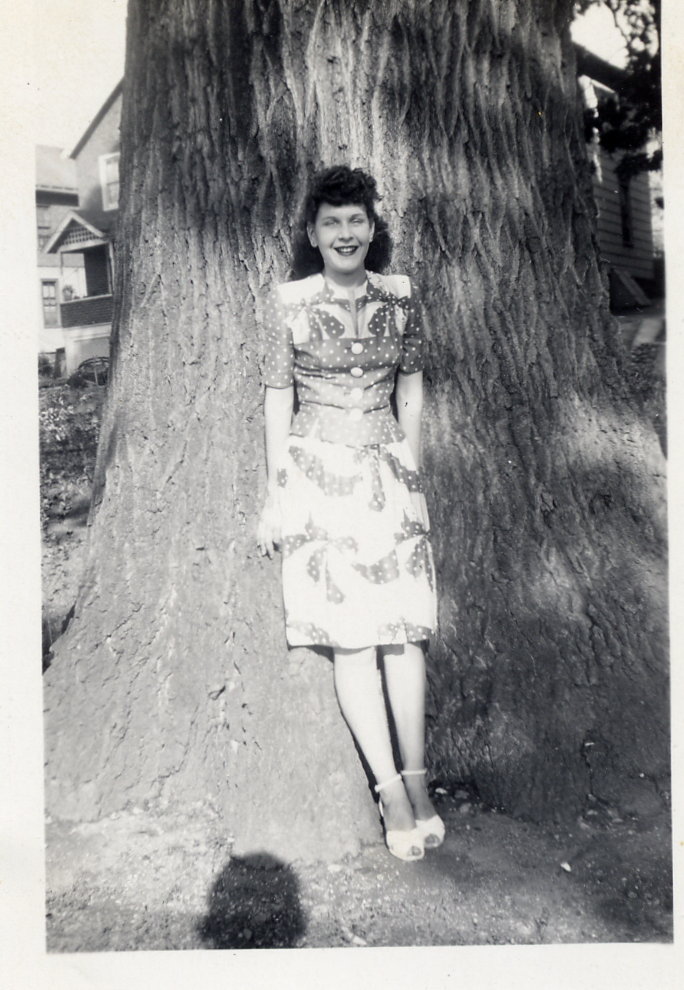

Mary had non-stop brown curls framing a pale complexion, light eyes and naturally rosy cheeks. Her scant 100 pounds was attractively distributed along a five-foot-two-inch frame. In short, she was a babe, a cutie pie among cutie pies.

At work, she wore a uniform of overalls and saddle shoes but she would dress up for after-work-outings. She enjoyed being “footloose and fancy-free”.

“I would go down to Seaside park,” she recalls. “There was a bathhouse and on Saturday nights they would have dances. And occasionally someone from work would say, ‘let’s go down to the dance.’”

These mixers were entertainment for servicemen and going to them was considered “something you did for the troops”. It worked well for the women too.

“You’ve got to remember there weren’t a lot of guys around to date. They were in the service and here was a dance hall with servicemen. You’d meet guys and sailors down there but I didn’t have a boyfriend, no one steady or anything.”

Lucy on the other hand did meet someone special at Chance Vought and soon she was married. The girls from Massachusetts moved back home and Mary, now on her own, went to live at a boarding house across the street. It was the family home of Liberty Schembari, a friend from the factory everyone called Libby.

She was pretty, petite and fun-loving and she and Mary often went to work together. Soon Libby’s parents Maria and Rosario Schembari were treating Mary like a daughter.

As the end of that first year in Connecticut approached, Libby told Mary that her brother, a deployed Navy sailor would be home for the holidays. The two should meet, Libby said. Mary agreed.

It was a fast courtship as Jimmy had just a few weeks of shore leave. By the summer of 1944, he was on the U.S. West Virginia when it rejoined the fleet after repairs to the damage it suffered in the attack on Pearl Harbor. In November 1945 he and Mary were married.

Sixty-five years later, along with Mary’s son Jim Schembari, who is my husband, we took Mary to the Connecticut Wheels and Wings Show at Sikorsky Memorial Airport. It was the 70th anniversary of the Corsair’s first flight. Five planes – all in airworthy condition – sat on the airfield under the adoring gaze of aviation geeks and history buffs. Among those appreciating the sight of the gleaming warplanes was the long-retired welder, my mother-in-law.

These fighters, which had been flown in combat in the Pacific might have helped to protect the Navy sailor who became Mary’s husband or provided air cover to the Marine who married Mary’s sister, Jo. She had constructed parts of these airplanes with her own hands barely aware of the significance of her work. As the afternoon went on, Mary battled her emotions as she watched pilots crank their engines and fly formations.

“It was an assembly line where you could see this thing being made,” she told me a few days later. “This plane is coming down and people are working on it. I didn’t have enough sense to look at it and realize what I was doing. I didn’t appreciate what I did until I stood there. I got choked up and I thought, ‘My God, this is what I did.’”

On December 24, Mary died. Though her time welding airplane parts was a small fraction of her long life, it had an outsized impact on her character. She took pride in the fact that she’d acquired a skill and supported her country. Heeding the advice of the newspaper-reading Sully, she remained informed about the world until the end.

Mary (Balestrini) Schembari was a wife and a mom. She was a mother-in-law, a grandmother, and a great-grandmother. She was a patriot and (Lord forgive them for the title) a Rosie the Riveter Congressional Gold Medal recipient. She has earned her place in aviation history.

Author of The New York Times bestseller, The Crash Detectives, I am also a journalist, public speaker and broadcaster specializing in aviation and travel.

Mary was a delight and served her country as well as she did her wonderful family. This story is a marvelous memory of her life. Thank you for sharing it. Condolences.

Thanks for sharing. May 24th is Aviation Maintenance Technician Day in celebration of people like Mary.

Great article. Well worth the read! Truly, a representative of a generation of Americans that made a difference. In the article, the wedding photo depicted is so powerful. Wondered what work her husband did after the War, where they lived, and so forth. Thanks for sharing.